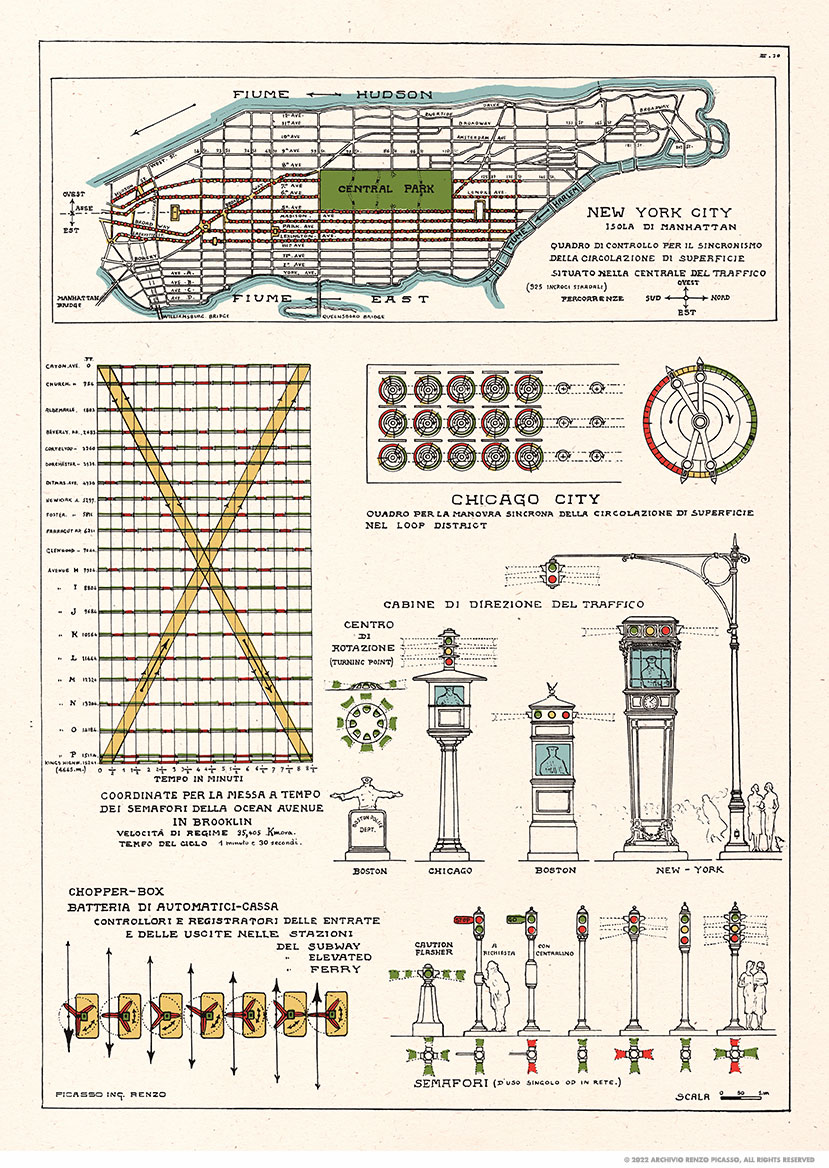

Included is a map of traffic light placement among New York's streets, dials used to control the changing of lights in Chicago's Loop District, various lights in use across different cities, pedestrian lights, a table for timing the lights on Brooklyn's Ocean Avenue, and, oddly, a turnstile used in subway station entrances. With the union of all these elements, Picasso pieced together a thorough guide on the use of traffic lights, especially for the installation of them. This is especially important due to how Picasso often uses his art as inspiration for the modernization of his home city of Genoa, particularly through the application of American engineering and transportation principles, as can be seen in this study. In addition, this plan was originally part of a three page set, titled “VEICOLI E REGOLATORI DI VIA,” alongside the intersections page and the vehicles page. As the set is labeled “Vehicles and Regulators of the Road,” the overall plan demonstrates the unison of the various technologies of transportation so that readers in Genoa who did not have access to these American technologies could obtain a thorough understanding of how these things overlap.

ON A CURIOUS NOTE:

Despite most of the plan being made up of details relating to traffic lights, Picasso included a drawing detailing the movement of turnstiles, which are used for the ingress and egress of human traffic within stations or parks. The most likely reason for this is that the function of a turnstile is to control human traffic, similarly to how traffic lights limit vehicular traffic. In addition, Picasso labels the speed of travel for Ocean Avenue as 35.4 km/hr, which is roughly 22 mph. At the time, this would be 8 mph (12.9 km/hr) under the speed limit, suggesting this is just a hypothetical to fill Picasso's example. Interestingly enough, this falls to 3 mph less than today's speed limit of 25 mph (40.2 km/hr), which was passed in 2014. Perhaps Picasso was a visionary for more than just his native Genoa.

Il disegno, disegnato dall'architetto italiano Renzo Picasso, mostra vari dettagli relativi all'uso dei semafori negli Stati Uniti tra la fine degli anni '20 e l'inizio degli anni '30.

È inclusa una mappa del posizionamento dei semafori tra le strade di New York, quadranti utilizzati per controllare il cambio delle luci nel Loop District di Chicago, varie luci in uso in diverse città, luci pedonali, una tabella per cronometrare le luci sulla Ocean Avenue di Brooklyn e, stranamente, un tornello utilizzato negli ingressi delle stazioni della metropolitana. Con l'unione di tutti questi elementi, Picasso mise insieme una guida approfondita sull'uso dei semafori, soprattutto per la loro installazione. Ciò è particolarmente importante perché Picasso usa spesso la sua arte come ispirazione per la modernizzazione della sua città natale, Genova, in particolare attraverso l'applicazione dei principi dell'ingegneria e dei trasporti americani, come si può vedere in questo studio.

Inoltre, questo piano era originariamente parte di un insieme di tre pagine, intitolato “VEICOLI E REGOLATORI DI VIA”, accanto alla pagina degli incroci e alla pagina dei veicoli. Poiché il set è etichettato come "Veicoli e regolatori della strada", il piano generale dimostra l'unisono delle varie tecnologie di trasporto in modo che i lettori a Genova che non avevano accesso a queste tecnologie americane potessero ottenere una comprensione approfondita di come queste cose si sovrappongono .

NOTA CURIOSA:

Nonostante la maggior parte del piano sia composto da dettagli relativi ai semafori, Picasso ha incluso un disegno che descrive in dettaglio il movimento dei tornelli, che vengono utilizzati per l'ingresso e l'uscita del traffico umano all'interno di stazioni o parchi. La ragione più probabile di ciò è che la funzione di un tornello è controllare il traffico umano, in modo simile a come i semafori limitano il traffico veicolare. Inoltre, Picasso etichetta la velocità di viaggio per Ocean Avenue come 35,4 km/h, che è di circa 22 mph. A quel tempo, questo sarebbe 8 mph (12,9 km/h) sotto il limite di velocità, suggerendo che questo è solo un ipotetico per riempire l'esempio di Picasso. È interessante notare che questo scende a 3 mph in meno rispetto al limite di velocità odierno di 25 mph (40,2 km / h), superato nel 2014. Forse Picasso era un visionario per qualcosa di più della sua nativa Genova.